Mr. Peabody and Sherman, the computer-animated movie which DreamWorks Animation released in March is–of course–the tale of a dog and a boy who go traveling back in time. So in a way, it’s appropriate that the proprietary software which the studio used to animate it, Emo, had a lot of history behind it.

Emo’s origins go back to the 1980s, an era in which computer graphics were very different than they are today, and DreamWorks didn’t even exist. It was created by Pacific Data Images, the company which, like Pixar, helped to pioneer the whole idea of digitally-generated entertainment. (PDI is now part of DreamWorks Animation.)

The next DreamWorks Animation feature after Peabody, How to Train Your Dragon 2, premiered last month. It’s the first movie which was produced using the studio’s new platform, Apollo, which includes a new animation system called Premo.

Apollo is one giant leap for DreamWorks; during a recent event at its studio in Redwood City, Calif., the company gave me and other journalists a behind-the-scenes show-and-tell.

Here’s a video DreamWorks Animation produced about the new software:

Very few computational projects of any sort gobble resources as voraciously as producing a computer-animated film. How to Train Your Dragon 2 is 102 minutes long, which translates into 130,000 frames of animation. Getting there involved 495 artists, 700 million files, 398 terabytes’ worth of data, and 90 million hours of rendering time.

And that’s just one movie. DreamWorks Animation has the most ambitious release schedule in the business: It’s currently working on thirteen features which it plans to release between now and November 2018. They’re all being done with Apollo and Premo, and the shift to the new platform is about time and money. But it also aims to put fewer technological barriers in between an artist’s raw creativity and a finished work of computer animation.

“Part of the mission was to create a more efficient way of working that would help shave production budgets,” says Dean DeBlois, who co-wrote and co-directed the original How to Train Your Dragon and wrote and directed the new film. “As it actually manifested itself, it allowed the animators to work so fast that they could go back and refine and finesse their work in this iterative process that they were not allowed to do in the past.”

The company started planning the new platform five years ago, at roughly the same time that it was beginning work on Dragon 2. From the beginning, it was a collaboration between the studio’s artists and its technologists, who worked together and aimed to create something with plenty of headroom for whatever the studio might dream up far into the future.

“We were able to say to them, ‘Don’t constrain yourself,” says Lincoln Wallen, DreamWorks Animation’s CTO. “It’s not about what the machines can deliver, it’s about how you want to work.”

Rex Grignon, DreamWorks Animation’s head of character animation–he started at PDI in 1988–says that the artists involved in creating Premo asked themselves “Why can’t I have an idea and touch the screen to get it there?” And as they hashed out plans for the new platform, they storyboarded them much as they’d do with an animated feature. “We literally cut out little pieces of paper and lists and things.”

Emo, the old animation software, required animators to convert the performances they envisioned into numbers which a computer could understand. For instance, making a character smile involved entering digits in a spreadsheet-like grid to specify adjustments to a character’s facial muscles. Artists could preview the results, but only in versions which stripped out so much detail that it could be tough to tell what a scene would look like on the screen.

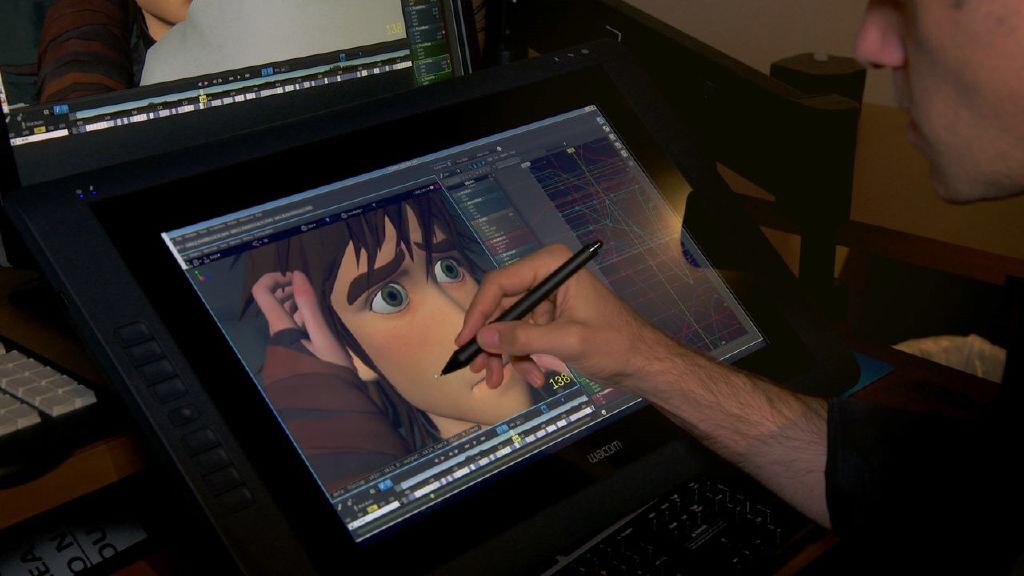

Premo lets DreamWorks’ artists animate by grabbing ahold of characters in a much more fully-rendered scene, using either a mouse or a Wacom Cintiq touch screen and stylus. They can nudge expressions into place, swing limbs around, and generally work in a much more direct fashion.

“Once [animators] have spent the couple of weeks it takes to learn how to really use Premo, they don’t want to go back,” says DeBlois.

Animators work on HP workstations with Intel Xeon processors. Though extremely well-equipped–they have 16 computing cores and 100GB of RAM–they’re off-the-shelf models which anyone can buy. Like the rest of the Apollo platform, they run Red Hat Linux.

Beyond the new creative possibilities opened up by Premo, the key fact about Apollo is that it aims to make all the tens of thousands of computing cores at Dreamworks’ disposal–on the artist’ workstations, the studio’s own server farms, and computing resources provided by HP as a service–behave like one seamless whole. It’s a massive cloud-computing project, which the studio developed with help from Intel, which has developed software libraries which enable the sort of distributed computing which the new platform relies on.

If something needs resources, Apollo is designed to be able to throw resources at it. If it requires a lot of resources, Apollo is designed to provide that, too. The end result is that it can make things which used to take a long time happen very, very fast.

In the past, for instance, it took 20 to 40 hours to render one theater-ready final frame of animation. With Apollo’s on-demand approach to computational horsepower, “I can turn the dial and reach 24 frames a second,” says Wallen.

That flexibility also allows the studio to push its drop-dead deadlines as far as possible: DeBlois told me that it was still wrapping up Dragon 2 on May 8. On May 16, the movie premiered at the Cannes Film Festival.

Nobody sitting in a theater is going to ponder the capabilities of the software behind the story. In fact, DeBlois says that the artists wanted to make the dragons so natural-looking that folks would even forget they were even watching a work of computer animation. But if Apollo and Premo didn’t exist, How to Train Your Dragon 2 wouldn’t be the movie that it is.

Let’s end this post with its first five minutes: