The Secret Origin of Windows

By Tandy Trower | Saturday, November 20, 2010 at 12:00 am

[A NOTE FROM HARRY: Windows 1.0 shipped on November 20th, 1985, which means that Microsoft’s operating system turns 25 today. Let’s celebrate by revisiting this fascinating look at Windows’ beginnings by Microsoft veteran Tandy Trower, which we originally published earlier this year.]

Few people understand Microsoft better than Tandy Trower, who worked at the company from 1981-2009. Trower was the product manager who ultimately shipped Windows 1.0, an endeavor that some advised him was a path toward a ruined career. Four product managers had already tried and failed to ship Windows before him, and he initially thought that he was being assigned an impossible task. In this follow-up to yesterday’s story on the future of Windows, Trower recounts the inside story of his experience in transforming Windows from vaporware into a product that has left an unmistakable imprint on the world, 25 years after it was first released.

Thanks to GUIdebook for letting us borrow many of the Windows images in this story.

–David Worthington

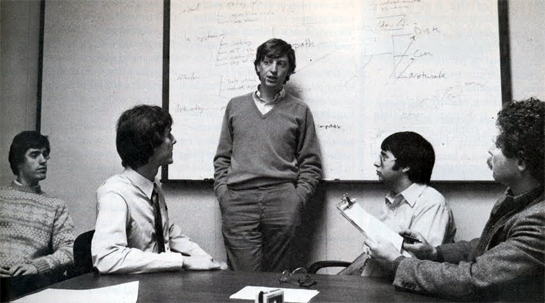

Microsoft staffers talk MS-DOS 2.0 with the editors of PC World in late 1982 or early 1983. Windows 1.0 wouldn’t ship for almost another two years. From left: Microsoft’s Chris Larson, PC World’s Steve Cook, Bill Gates, Tandy Trower, and founding PC World editor Andrew Fluegelman.

In the late fall of 1984, I was just past three years in my employment with Microsoft. Considering the revolving doors in Silicon Valley at that time, I already had met or exceeded the typical time of employment with a high-tech company. Over that time I already had established a good track record, having started with product management of Microsoft’s flagship product, BASIC, and successfully introduced many versions including the so-called GW-BASIC which was licensed to PC clone vendors, various BASIC compilers, and a BASIC interpreter and compiler for the Apple Macintosh. As a result I had been given the overall responsibility for managingMicrosoft’s programming languages, which included FORTRAN, Pascal, COBOL, 8086 Macro Assembler, and its first C compiler for MS-DOS. It was at this point that things took a significant turn.

I had just gone through one of those infamous grueling project reviews with Bill Gates, who was known for his ability to cover all details related to product strategy, not only those on the technical side. Borland’s Turbo Pascal had just come out, seemed to be taking the market by storm, and looked like a possible competitor to Microsoft BASIC as the language that was shipped with every PC. While Microsoft had its own version of Pascal, it had been groomed as a professional developer’s tool, and in fact was the core language Microsoft wrote many of its own software products in before it was displaced by C.

Bill Gates made it quite clear that he was not happy.

At $50 for the Borland product vs. the Microsoft $400 compiler, it was a bit like comparing a VW to a Porsche. But while Turbo Pascal was lighter weight for serious development, it was almost as quick for programming and debugging as Microsoft’s BASIC interpreters. And Pascal was the programming language that most computer science students most typically studied. The new Borland product would require serious strategy revisions to the existing plans to port Microsoft Pascal to a new compiler architecture. But it also required thinking about how to address this with our BASIC products. Could a Turbo BASIC be on the horizon? In any case, Gates made it quite clear that he was not happy .

Returning to my office I was somewhat devastated. In the days that followed, as I tried to come up with a revised strategy, I was uncertain about whether I should even continue in this role. I had come to Microsoft from a consumer computer company where I had primarily managed a variety of entertainment and education software. Even in my early career at Microsoft I had managed its early PC games like Flight Simulator, Decathlon, and Typing Tutor. And I had loved managing BASIC, not just because it was the product the company was best known for, but because BASIC helped me get my own start in the PC business, and I believed it allowed a wide audience to tap into the power of PCs. Now my job had evolved to where I was managing a family of products mostly for a highly technical audience. So, I spoke with Steve Ballmer, then my direct manager and head of Microsoft’s product marketing group, and suggested that perhaps I was the wrong person for this job.

A couple of weeks later, Ballmer called me in and proposed that I transfer over to manage Windows. Sounds like a plum job right? Well, that wasn’t so obvious at the time. Windows had been announced the previous year with much fanfare and support from most of the existing PC vendors. However, by the time of my discussion with Steve, Windows still had not shipped within the promised timeframe and was starting to earn the reputation of being “vaporware.” In fact Ballmer had just returned from what we internally referred to as the “mea culpa” tour to personally apologize to analysts and press for the product not having shipped on time and to reinforce Microsoft’s definite plans to complete it soon.

Windows was developing a reputation for career death.

Further, Microsoft’s strategy to get IBM to license Windows had failed. IBM had rejected Windows in favor of its own character-based DOS application windowing product called TopView. With IBM still the dominant PC seller, Microsoft would have to market Windows directly to IBM PC users. It would be the first time the company sold an OS level product directly to end-users (unless you count the Apple SoftCard, a hardware card that enabled Apple II users to run CPM-80 applications on their Apple IIs, which I had also previously managed). Since I had been the product manager that had the most experience with marketing technically oriented products through retail channels (rather licensed to PC vendors), Ballmer thought the job might be a good fit. In addition, he pointed out that since Windows was intended to expand the appeal of PC through its easier-to-use graphical user interface, it should appeal to my more end-user product experience and interests.

At that point Windows was no longer considered the company’s star project, as it had become a bit of an embarrassment. Even internally there were doubts among some in the company that Windows would ever ship. Also, because Ballmer had already burned though four product managers to try to get there–people who now had been either reassigned or were no longer at Microsoft–the product was developing a reputation for career death. Apparently prior to offering the job to me, Ballmer had tried to persuade Rob Glaser, already recognized as a bright, up-and coming talent, to take the position. But Glaser turned him down. When Glaser heard that I was offered the position, he even stopped by to counsel might that it would be a bad career move.

At that point Windows was no longer considered the company’s star project, as it had become a bit of an embarrassment. Even internally there were doubts among some in the company that Windows would ever ship. Also, because Ballmer had already burned though four product managers to try to get there–people who now had been either reassigned or were no longer at Microsoft–the product was developing a reputation for career death. Apparently prior to offering the job to me, Ballmer had tried to persuade Rob Glaser, already recognized as a bright, up-and coming talent, to take the position. But Glaser turned him down. When Glaser heard that I was offered the position, he even stopped by to counsel might that it would be a bad career move.

This made me think that perhaps the offer to me was a ploy by Gates and Ballmer to fire me because of their disappointment in dealing with Turbo Pascal and my suggestion that perhaps my assignment to managing programming languages was a poor choice on their part. It seemed clever: give me a task that no one else had succeeded with, let me fail as well, and they would have not only a scapegoat, but easy grounds to terminate me. So, I confronted Gates and Ballmer about my theory. After their somewhat raucous laughter they regained their composure and assured me that the offer was sincere and that they had confidence in my potential success.

So, in January of 1985 I transitioned over the Windows team, but even as I assumed my new role, I discovered that the Windows development architect and manager, Scott McGregor, a former Xerox PARC engineer, has just resigned. Ballmer himself took up McGregor’s role as the development lead in addition to his other responsibilities.

Shaping Up Windows

My first task was to assess of what was done and what was left to be done as well as come up with a marketing strategy of how to sell an OS add-on to end users, a task that was a significant challenge because no Windows applications existed at that time. How to sell a new application interface without any applications?

I discovered that while the three core functional components of Windows (Kernel–memory management, User–windowing and controls, and GDI–device rendering) were mostly in place there was still a substantial amount of work to be done, and Ballmer had given me only six months to finalize the product and get out the door. This didn’t bother too much since I had currently held the record for getting a product from definition to market in the shortest time.

Windows needed to be finished, not further tweaked in any way that jeopardized getting it out that summer without further embarrassment.

There wasn’t much time to make changes. Ballmer was emphatic not to redefine what was already done, even though McGregor had changed Windows from its original overlapping windows design to a tiled windows model and every windowing system out there or under development featured overlapping windows. There also was not enough time to change the Windows system font displayed in title bars and control labels from a fixed width typeface to a proportional typeface, which made the overall look a bit clunky, especially in comparison to the newly announced Macintosh interface. Steve’s promise was that in the next release I would get creative freedom to make any significant changes to the product’s interface. I could add some functionality to make it more appealing to end-users, but overall the product needed to be finished, not further tweaked in any way that jeopardized getting it out that summer without further embarrassment.

1 2 3 NEXT PAGE»

6 Comments

Read more:

November 21st, 2010 at 2:02 pm

I remember back in 1986 when Apple was against Atari and Apple like stole the GEM operating system (They claim modeled after) and Atari bought legal rights tio use. I traded my Atari 800XL system in for a NEC V-30286 like) laptop. Friends used Windows 2.0 & 3.0, finally bought Windows 3.1. But that was after giving up on authoring my own Click and drop software in Turbo Pascal. GEM was nice but never got close to Windows 3.1 but it was a nice GUI.

By the way did anyone ever see the movie of Bill Gates -vs- the Apple founders made by one of the cable Superstitions just before Windows 3.1 came out in 1995. Do not recall the movie title, but have a DVD copy of it. It may only be 70% factual truth but gives a good idea of the Windows wars in the 80's and 90's.

And if you do not know or are a denying MAChead, Windows and Bill Gates one the battle.

November 24th, 2010 at 5:32 pm

I think that was "Pirates of Silicon Valley", but it was released closer to 2000, if I remember correctly. I remember watching that as a high school student.

November 22nd, 2010 at 12:47 am

I was born in 1981, and just wondering how windows has been change my way in using a computer. thanks microsoft!

December 31st, 2010 at 5:15 pm

Windows '95 (not Windows 3.1, which was essentially a DOS shell) was a complete rip-off of the Mac operating system. Not a good rip off, but a rip off. Scully, after getting rid of the company founder, brokered a deal that allowed MS to do this, and then sued when he discovered his pants were unzipped and lost. Sans that suit, no Windows. As for who won what, Gates versus Jobs, that's like comparing Louie B. Mayer and Walt Disney. You may or may not like Walt Disney (the man could not draw a lick), he was a brilliant visionary while LB Mayer ran a studio. If you are having trouble deciding who was who, Gates versus Jobs, well, Gates rans a studio.

August 21st, 2011 at 1:28 pm

And now Steve Jobs is the biggest stockholder of Walt Disney – and Apple is bigger than Microsoft, Intel, and Google, combined…

January 31st, 2012 at 7:08 am

I love Mac operating system. Not a good rip off, but a rip off. Scully, after getting rid of the company founder, brokered a deal that allowed MS to do this, and then sued when he discovered his pants were unzipped and lost. Sans that suit, no Windows. As for who won what, Gates versus Jobs, that's like comparing Louie B. Mayer and Walt Disney. You may or may not like Walt Disney (the man could not draw a lick), he was a brilliant visionary while LB Mayer ran a studio. If you are having trouble deciding who was who, Gates versus Jobs, well, Gates rans a studio.