Computer Space and the Dawn of the Arcade Video Game

How a little-known 1971 machine launched an industry.By Benj Edwards | Sunday, December 11, 2011 at 10:14 pm

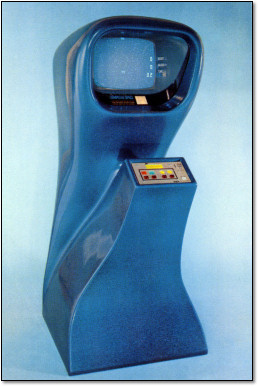

Forty years ago, Nutting Associates released the world’s first mass-produced and commercially sold video game, Computer Space. It was the brainchild of Nolan Bushnell, a charismatic engineer with a creative vision matched only by his skill at self-promotion. With the help of his business partner Ted Dabney and the staff of Nutting Associates, Bushnell pushed the game from nothing into reality only two short years after conceiving the idea.

Forty years ago, Nutting Associates released the world’s first mass-produced and commercially sold video game, Computer Space. It was the brainchild of Nolan Bushnell, a charismatic engineer with a creative vision matched only by his skill at self-promotion. With the help of his business partner Ted Dabney and the staff of Nutting Associates, Bushnell pushed the game from nothing into reality only two short years after conceiving the idea.

Computer Space pitted a player-controlled rocket ship against two machine-controlled flying saucers in a space simulation set before a two-dimensional star field. The player controlled the rocket with four buttons: one for fire, which shoots a missile from the front of the rocket ship; two directional rotation buttons (to rotate the ship orientation clockwise or counterclockwise); and one for thrust, which propelled the ship in whichever direction it happened to be pointing. Think of Asteroids without the asteroids, and you should get the picture.

During play, two saucers would appear on the screen and shoot at the player while flying in a zig-zag formation. The player’s goal was to dodge the saucer fire and shoot the saucers.

Considering a game of this complexity playing out on a TV set, you might think that it was created as a sophisticated piece of software running on a computer. You’d think it, but you’d be wrong–and Bushnell wouldn’t blame you for the mistake. How he and Dabney managed to pull it off is a story of audacity, tenacity, and sheer force-of-will worthy of tech legend. This is how it happened.

The Germ of an Idea

The genesis of Computer Space dates back to 1962, when a group of computer enthusiasts at MIT created the world’s first known action video game. They called it “Spacewar!” (the exclamation mark was their idea too). It pitted two human-controlled ships against each other in a physics-based space duel that played out on the $20,000 vector display of a $120,000 DEC PDP-1 computer. For those of you keeping score, that totals up to over $1 million in 2011 dollars when adjusted for inflation.

Spacewar became very popular among computer users at MIT, and it soon caught the attention of Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), the company that manufactured the PDP-1. Not long after its release, DEC began to distribute Spacewar as a glorified tech demo for PDP-series computers, which spread the game’s code to universities around the world. Over the next few years, fans ported the game to nearly every computer with a vector display, although those were admittedly few and far between–in the 1960s, most universities only owned one or two computers total; the machines were so expensive that only large organizations could afford them.

Two men playing Spacewar! on a PDP-1, circa 1962. (Photo: DEC)

In 1964, a young engineering student named Nolan Kay Bushnell encountered Spacewar for the first time at the University of Utah, which he attended. He found himself completely enraptured and could hardly pull himself away from the computer. “I loved the game and played it every chance I could get,” recalls Bushnell. “I didn’t get as many chances as I wanted.”

At the time, Bushnell worked a summer job as manager of the games department at the Lagoon Amusement Park in Farmington, Utah. There he saw electromechanical coin-operated arcade games that offered completely automated, interactive game experiences.

Arcade Games: Then & Now

Prior to video games, reliability issues drastically limited the size of the coin-operated game market. Bushnell explains it this way:

“Mechanical games had a mean time between failures that was in the level of days. It really destroyed the economic viability of having a remote machine. But if you had an arcade that had a mechanic there that was able to fix them, it made perfect sense. ‘Cause the failures that they’d have would not necessarily be parts–it’d just be contacts getting out of alignment or little piddily things. They were so complex that there were a lot of little things to go wrong.”

Video games, with their solid-state construction, represented a new wave of reliability for arcade machines, allowing the market to significantly expand.

At that time, pinball machines dominated the coin-operated arcade game market, but manufacturers also offered shooting gallery, racing, and other crude games. Such games relied upon a postwar toolkit of relays, electromechanical components, film projectors, and transparencies to achieve the desired game play and visual effects, and they were prone to breaking down at any moment.

After seeing Spacewar, it occurred to Bushnell that the sci-fi computer game could form the basis for an amazing coin-op arcade machine. But the bright idea was soon followed by the realization that, with computer prices as high as they were, the game simply wouldn’t work as a commercial product. He filed it away in the back of his mind and moved on.

After graduating from University of Utah with a BSEE degree in 1968, Bushnell landed a job at Ampex in California. By that point Ampex had made its name as a prominent audio and video recording technology company; its innovations included the first multi-track audio recorder and the commercial video tape recorder. Bushnell packed up his things and moved out to the west coast, never looking back. He was 25 years old.

Bushnell (L) and Dabney (R) in 1972.

On his first day at Ampex as an engineer on the Videofile project, Bushnell met his new office mate, 31 year-old Samuel Frederick Dabney, Jr., known as “Ted” for short.

“I thought he was a nice guy, pretty straightforward, pretty level-headed,” recalls Dabney of Bushnell, whose charm and charisma always seemed to precede any practical engineering skills he might have. “I couldn’t quite figure out what he was capable of doing because, whenever I would ask him a question, he would ask me a question.”

The Stigma of the Arcade

In the 1960s, coin-operated arcade games carried with them a hint of moral stigma due to their perceived relationship to mechanized gambling. Bally, a prominent pinball and coin-operated amusements manufacturer, dominated the market for slot machines throughout the 1960s, eventually opening its own Vegas casino.

Bushnell dreamed of erasing that stigma by bringing the games into a family friendly restaurant atmosphere that would include arcade games, Skee-Ball, and talking barrels (that idea, however strange, evolved into animatronic singing animals). The concept later inspired Chuck E. Cheese’s Pizza Time Theatres, the first of which opened in 1977.

Bushnell recalls Dabney as “a really, really nice guy. Smart guy. Self-taught, but just full of practical knowledge.”

The two hit it off, and Bushnell soon introduced Dabney to his love of board games. The two engineers played chess at first — mostly during office hours — but soon branched out to go, a complex Chinese board game that was immensely popular in Japan.

To facilitate their regular in-office gaming sessions, Dabney built a go board with an Ampex logo on the back for camouflage. They would set the board on a trash can between their desks while playing, and if management came along, they would flip the board over and hang it on the wall, logo-side out, so no one would know what they were up to.

While playing these games, Dabney says that Bushnell shared his dreams of creating a family-friendly amusement restaurant that would bring coin-operated games out of amusement parks and into the mainstream. The pair examined the concept in detail, even visiting some restaurants together for research. They decided not to act on the idea (for the moment), but it marked the beginning of their plans to go into business together.

The Epiphany

While navigating the Silicon Valley social scene, Bushnell made friends with a computer engineer named Jim Stein who worked at Stanford’s Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (yes, they were already researching AI in 1969). The lab owned its very own PDP-6 computer and an I3 vector display, which prompted Bushnell to inquire if it could run Spacewar. Stein said yes, and the pair spent hours playing the game on one of the Ampex engineer’s night visits.

Bushnell’s First Video Games

While Bushnell attended the University of Utah, he was so enamored with the school’s PDP-series computer system that he began to program games for it in Forth. He created a baseball game and a version of the classic peg puzzle called “fox and geese,” both of which utilized the computer’s vector display. Unfortunately, the games, which were stored on stacks of punched cards, ended up in the trash can when he moved to California a few years later.

Not long after, Bushnell ran across an ad for the new Data General Nova minicomputer in one of his engineering magazines. As one of the lowest-cost minicomputers on the market (a stripped-down base model cost a mere $3,995–roughly $24,600 today), the Nova represented a new era in computing. Bushnell realized that an economically justifiable coin-operated computer game might finally be within his reach.

It wasn’t long before Bushnell dragged Dabney down to the lab to see Spacewar, which Bushnell enthusiastically gushed over. It was then that Bushnell revealed his ideas for a commercial computer game to Dabney. “He said, ‘We’ve got to put a coin slot on that thing,'” recalls Dabney. The self-taught engineer wasn’t too impressed with Spacewar itself, but he wasn’t about to back away from an interesting technical challenge either.

The pair began discussing what it would take to make Bushnell’s idea a reality. “We knew we needed a computer, so we needed a computer programmer,” says Dabney. They enlisted Larry Bryan, another Ampex engineer as their “computer guy.” The trio decided to form a company; Bryan came up the with name Syzygy, an astronomy term for a straight-line configuration of three celestial bodies. Each would deposit $100 into a group bank account to get started.

That was the plan, anyway. Bushnell and Dabney put in their money, but Bryan never did. It actually worked out for the best, because the “computer guy” soon became superfluous to the project. To better make use of a costly minicomputer, Bushnell had planned to hook two game-playing stations to one Nova, which would play two separate games simultaneously. Bushnell worked out the math and found that the Nova, the only computer they could dream of affording, was too slow to meet their needs.

After that, the idea died down. Months went by and Dabney figured their plan to make a computer arcade machine would never materialize. But Bushnell would not be deterred. Dabney recalls the scene of Bushnell’s breakthrough epiphany.

“Nolan came to me one time and he said, ‘On a TV set, when you turn the vertical hold on the TV, the picture will go up, and if you turn it the other way, it goes down. Why does it do that?’ I explained it to him. It was the difference between the sync and the picture timing. He said, ‘Could we do that with some control?’ I said, ‘Yeah, we probably can, but we’d have to do it digitally, because analog would not be linear.'”

What Bushnell had hit upon was an idea to electronically manipulate the video signal of an ordinary television set so they could play an interactive electronic game without the need for a computer. It wasn’t the first time in history that someone had made that realization; Ralph Baer, an engineer at Sanders Associates, had invented the first TV video games in 1967, but Bushnell had no knowledge of that prior discovery.

Bushnell asked his friend if he could put together a prototype that could do exactly what he had described, and Dabney took up the challenge. Dabney moved his eldest daughter, Terri, into a smaller bedroom and requisitioned her old sleeping space as a lab where he could implement his ideas. Working completely alone, Dabney built a circuit board that could display a single spot on a TV set while allowing a user to move the spot around using switches. “My neighbors would come over and see what I was doing, and they would start laughing at how funny that looked,” says Dabney.

Dabney showed Bushnell his work, completed in the fall of 1969, and the younger engineer was impressed. He handed over the board to Bushnell for further tinkering and forgot about it for the moment, becoming re-absorbed in his work at Ampex. Meanwhile, Bushnell had big plans for Dabney’s new invention.

Enter Nutting Associates

By early 1970, Bushnell had already been brainstorming about how to turn Dabney’s video control board into a shipping game. He decided that he needed investment from an outside source to make his dream of a coin-operated video game a reality, but he had no connections in the arcade industry.

The opportunity Bushnell needed fell into his lap in February 1970 during a visit to the dentist. While getting his teeth checked out, Bushnell described his current project to the doctor, who recalled a patient of his that worked as marketing director for a local coin-op game company.

That patient happened to be Dave Ralston of Nutting Associates, a small arcade game maker based in Mountain View. Nutting’s marquee product at the time was Computer Quiz, a general trivia arcade machine that projected questions onto a screen and allowed users to choose answers with push button controls. (No computers were actually involved.)

Bushnell called Ralston, and two days later he was in Nutting Associates’ offices pitching to both Ralston and Bill Nutting, president of the company, on his idea for a coin-operated Spacewar game. At the time, Nutting Associates was in financial decline, almost wholly dependent on its three-year-old Computer Quiz game to get by. The pair were anxious for another product to revive their business, so they said yes to Bushnell’s idea while also extending an offer to hire him as chief engineer of Nutting.

Sensing Nutting’s desperation, Bushnell pitched an amazingly lopsided deal that allowed him and Dabney to retain the rights to Computer Space, licensing it to Nutting for production in exchange for a 5% royalty on unit sales — even though Bushnell would develop the game as an employee. Nutting would provide the facilities for Computer Space’s development and pay its manufacturing costs.

“I was very careful,” recalls Bushnell. “In my employment contract, I excluded the video game technology and all the shop right issues and told them that I would not work on the design of the video game on their time until it was ready to be put into production, which is something that I would allow them to pay for.”

Before Bushnell came along, Nutting Associates had no in-house capability to design a game for itself. Computer Quiz had been created by Bill Nutting’s brother, David, who lived in Chicago and operated his own amusements company. “They didn’t have an engineering staff,” says Dabney, “and they didn’t have anybody that understood how to fix their machines when they broke. Nolan convinced him he could do that.”

So, in a sense, Bushnell became Nutting’s engineering department when he joined Nutting in March 1970, quitting his job at Ampex without a second thought. Meanwhile, Dabney stayed behind at his old employer. He wasn’t ready to give up his secure job for a risky proposition — yet.

Bushnell, on the other hand, was convinced that video-based arcade games were the future of the arcade amusement industry. They would be solid state, having no moving parts other than the controls, so they would be easy to deploy and maintain. At Nutting, he set out to build the first coin-operated video game ever created. As it turned out, he wasn’t completely alone.

A Coincidence Six Miles Away

Around the time Bushnell started developing Computer Space at Nutting, a Stanford alumnus and his high school buddy had just begun work on their own coin-operated version of Spacewar. Unlike Bushnell’s version, their game would rely on a real computer to function.

In 1971, Bill Pitts and Hugh Tuck bought a $14,000 DEC PDP-11/20 minicomputer and a $3,000 vector display with money gathered from family and friends. Tuck built controls and enclosures while Pitts began programming a custom reproduction of Spacewar with the goal of creating a coin-munching pay-to-play amusement device.

With the “war” in “Spacewar” being an unpopular subject on university campuses at the time, they chose the title “Galaxy Game” to describe their work.

Just as Tuck and Pitts were finalizing their game, they received a call from Nolan Bushnell, who had heard about Galaxy Game through mutual contacts. Neither party knew of the other’s effort when they started, so Bushnell was understandably intrigued.

“I can remember thinking ‘Gee, I’ve got to meet with these guys,'” recalls Bushnell. Over coffee at Stanford, the Nutting engineer told Galaxy Game’s creators about his plans for Computer Space and invited them over to Nutting’s offices to take a look.

“We went in there and Nolan was literally an engineer with an oscilloscope in hand working on Computer Space,” said Pitts in an interview with Tristan Donovan for the book Replay: The History of Video Games. Pitts and Tuck were impressed with what Bushnell was pulling off technologically, but they felt their game was superior because it was true to Spacewar.

1 2 3 NEXT PAGE»

Comments are closed

Read more:

December 11th, 2011 at 11:47 pm

What a cool story. Almost Jobsian in its emphasis on vision, focus and intentionality. I was familiar with Pong, but did not know about Computer Space. Thanks for sharing this.

December 13th, 2011 at 11:15 pm

I think it's the other way around since Jobs and Woz worked for Bushnell on Breakout. You should say it's 'Bushnellian".

December 14th, 2011 at 5:47 am

Exactly.

December 12th, 2011 at 3:36 am

The 1st time I played "Space War!" was on a PDP-11. I remember running into a Space War arcade game in the '70's that was a clone of the DEC version. Required 2 players as you couldn't play against the computer. This was back when Silicon Valley was actually that. Unlike today.

December 12th, 2011 at 4:55 am

I worked for Nolan, went out to CA for a couple weeks, he took me to the first Chuck E. Cheese. Atari was like a family back in those days. Very cool times.

December 12th, 2011 at 6:49 am

I played Pong on holiday in Hawaii in 1973. I was four years old and stood on a milk crate so I could see the screen. Obviously, at the time, I had no idea what a revolutionary thing this was.

December 12th, 2011 at 8:12 am

Heh. First video game I ever played–before Pong and, in my opinion, better.

December 12th, 2011 at 12:21 pm

Outstanding story, thanks for posting it. I'm fascinated by video game history, but somehow I knew nothing of this. I've read various histories of Space War and Pong (and played the original arcade versions of both), but the histories didn't mention Computer Space as being the game that came in between and sort of bridged the gap. Impressive engineering by Bushnell & Dabney.

December 12th, 2011 at 1:25 pm

great story, thanks for sharing.

December 13th, 2011 at 4:16 am

Well researched article that gets the “Dabney” factor across very well.

Our podcast did the first interview with Ted Dabney where he tells the whole story. We later interviewed Al Alcorn who built the follow up game, Pong.

We are now trying to get Nolan but he has so far not agreed to come on.

I hope he does.

December 13th, 2011 at 9:59 am

Excellent article! I run that website with the simulator on it and I'm happy to see people showing excitement for Computer Space again.

(and I think I better make my simulator page look nicer if people visit it from this article)

December 13th, 2011 at 10:26 am

When I read The_Heraclitus's comment, it brought back memories of my first playing "Space War", as mine also was on a PDP-11. While working at Johnson's Space Center at Houston, Texas in 1973, one of the many computers I had responsibilities of maintaining was a PDP-11. Its main function was to create vector images displayed on monitors mounted in the window of an early space shuttle flight deck mockup. Of the many programs stored on its dual disk drive platters was “Space War”. While it was very archaic by today’s possibilities, It seemed way ahead of its time back then.

December 13th, 2011 at 11:18 pm

Anytime I hear stories about the old days, I get all sentimental. It's sad what happened to Atari and Nolan Bushnell deserves more praise for his contributions. He is a foundational figure in the history of silicon valley and technology as we know it.

December 13th, 2011 at 11:21 pm

In 1967 I started my first job, at Elliott Bros Automation int he UK. I was introduced to Space War running on the Elliott 4130's Vector Graphics display my first week there. I was very impressed, as much by the game as the fact that there we were, occupying 100% of a very expensive machine's time. But doing that turned out to be one of the perks of working for the manufacturer of the computer. I had one that I could call my first "Personal Computer" in that I had control of the power switch, and permission to do whatever I wanted with it after 5 pm. Haven't stopped since…

December 31st, 2011 at 10:11 am

Wonderful, wonderful article. I have vague memories of playing Pong as a small child in the early `70's, and clearer memories of playing the 2-player Space War arcade game a few years later. Being a huge fan of retrogaming, I'd heard of Computer Space (and even played it at a traveling video game exhibit at our local science museum about 15 years ago!), but didn't know the full story behind its development. I'm also delighted by the mention of Sega Missile, which is nearly identical to an electromechanical game called S.A.M.I. that I also played as a small child. Pure joy!

February 5th, 2012 at 8:53 pm

Some of the information in this is self serving. Just after he completed the third generation (the first solid sate coin op game) of Computer Quiz, and a new color question film strip series was ready, Richard Ball, Industrial Designer overseeing the upgrades, went to Bill Nutting and said that his projections for Computer Quiz were that in a little over a year they would be down to a one woman assembly line. Nutting said, "Well do something about it!" The result was a concept, marketing and design brief for a coin op video game "Space Command". A second brief was a form of play station to be used in bars. Shortly after Nutting bought another airplane at company expense. Ransome White, a Stanford MBA, and Ball objected. They were fired, Ball was asked to come back, but went on to cofound Cointronics with Ransome White. Cointronic's audio reward game, the first to have a taped message, Lunar Lander came out about the time the Computer Space was introduced. Nutting found Bushlnell sometime after Ball and White went out on their own. Ball left the Coin Op field when he found out the MAFIA controlled the industry. He went on to found Enrich an educational corporation. When at a later time Bushnell decided to make coin op games for his Chuckee Cheese locations the mob slapped his wrist. After they had put Nutting and Cointronics into bankruptcy the only games available were from Balley, Midway, Atari and Sega. All of these corporations has dubious connections.